Sunday mornings arrive without noise. They carry a stillness that urges you to walk, not rush; to look inward before looking ahead. One such morning began with a quiet step into Downtown Srinagar and slowly unfolded into a journey back to where memory, history, and identity continue to reside softly, stubbornly.

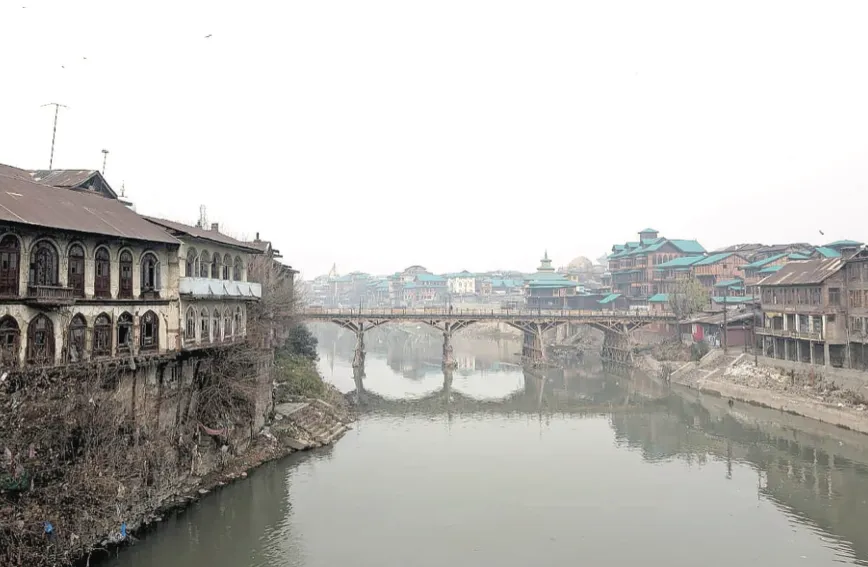

Along with a dear friend, Murtuza Habib, I set out to explore the downtown quarters on a Sunday, hoping to understand our past, our history, and, ultimately, our people. We began in the wee hours at Habba Kadal (Purshar), where the Jhelum still whispers its stories to bridges that have held centuries together. From there, the lanes gently guided us through Karfali Mohalla, Dal Hassan Bhat, Mallarut, Bul Bul Lankar, and beyond—each turn offering a sense of familiar unfamiliarity.

Zaina Kadal, Fateh Kadal, Aali Kadal, Nawa Kadal—these are not merely locations. They are chapters in a living archive. This was not just a walk through historical lanes and by-lanes; it was a reminder of how far we have come as a society and as a community. At times, the realization felt encouraging; at others, deeply unsettling.

Walking becomes especially engaging when the filmmaker within you stays alert—drawn to old motifs, architectural marvels, and human faces etched with time. Listening to people’s stories was among the most fascinating aspects of this early-morning journey. The lanes and structures do not merely stand as testimony; they speak—of yesteryears, of lives lived with purpose and rhythm. The traditional Jhelum ghats beneath each iconic bridge offer fleeting glimpses into history, though they also reveal a sorry state of affairs. The embankments cry out for rigorous cleaning drives. Places of faith—temples, shrines, and Masjids—must become spaces where people are educated about cleanliness and a shared sense of belonging.

By the time we reached Narwara and Eidgah, the morning had transformed into a meditation on belonging. These localities are home to some of the finest craftsmen. This time, we chose not to visit Zadibal, the adjacent area known for masters of papier-mâché, calligraphy, and sokhta making. That detour would surely have carried us into another world altogether.

Downtown does not announce itself. It reveals itself—slowly, honestly, almost defiantly. In its narrow alleys and winding by-lanes, history breathes through brick and timber. Ancient houses lean gently into one another, as if sharing secrets. Markets—some freshly refurbished, others weary with age—stand side by side, reflecting both promise and neglect. Along the ghats, beauty struggles beneath layers of waste, a painful contrast to the elegance they once embodied.

There is silence here, but it is not emptiness. It is the silence of graveyards where generations rest; of shrines, temples, and masjids standing in quiet dignity; of people moving through routines shaped by centuries. This is a place where faiths have long coexisted, where art and craft once defined everyday life, where artisans shaped not only objects but culture itself.

And yet, as the walk deepened, so did a sense of discomfort. Neglect is undeniable. Faulty waste management has stripped Downtown of its aura, dulling its spirit and burdening its beauty. Dirty lanes and overflowing ghats are not merely civic failures—they are emotional ruptures. They distance us from our roots, from spaces that once defined who we are.

Why does Downtown Srinagar need a revamp?

Downtown Srinagar urgently needs a thoughtful and sensitive revamp because it embodies the city’s deepest historical, cultural, and environmental identity – an identity that is gradually being lost. For centuries, this area has been the heart of Srinagar’s river-based civilization, shaped by the Jhelum, traditional livelihoods, and a distinctive vernacular architecture. The old mud-and-wood houses, designed with remarkable climatic intelligence, provided natural insulation, sustainability, and resilience long before modern concepts of green architecture emerged.

However, years of neglect and unplanned modernization have severely eroded this legacy. Haphazard concrete structures have replaced traditional buildings, disrupting the visual harmony of the area and weakening its cultural continuity. These constructions not only appear as visual intrusions but also undermine environmental balance, as they ignore local materials, climate conditions, and traditional building wisdom. As a result, Downtown’s character—once defined by craftsmanship, spatial intimacy, and cultural memory is steadily fading.

Despite this decline, there have been meaningful efforts to reintroduce Downtown Srinagar to wider cultural and artistic discourse. The former Director of the Department of Handicrafts and Handlooms, and a dear friend, Mahmod A. Shah, played a crucial role in initiating programs such as the Downtown Craft Safari and calligraphy exhibitions. These initiatives helped expose the area’s rich artisanal heritage and revived interest in its creative potential. Many of my artist and filmmaker friends have since expressed a strong desire to explore Downtown’s artistic, cultural, and cinematic dimensions further, recognizing it as an untapped space of inspiration and storytelling.

The need for a revamp, therefore, is not about cosmetic beautification or aggressive redevelopment. It is about reclaiming Downtown Srinagar’s past with sensitivity and respect, and using that foundation to shape a more rooted, inclusive, and sustainable future. Revitalizing this historic core means preserving its architectural wisdom, supporting local crafts, encouraging cultural engagement, and restoring its connection to the river and community life. Only by doing so can Downtown Srinagar regain its rightful place as the living soul of the city rather than a forgotten relic.

Still, hope lingers

Downtown does not need reinvention; it needs reclamation. What it calls for is careful rebooting and sensitive rebranding—without altering its soul. As we celebrate startups and innovation, we must also extend our hands to the artisans whose skills are fading in silence. Supporting them is not charity; it is continuity. Their survival ensures that Downtown remains a living heritage, not a museum of memories.

This walk was more than a tour; it was a reckoning. Before we promote, beautify, or commercialize, we must first own Downtown in its entirety—own it with responsibility, with respect, and with care. Its streets hold far more than what meets the eye. There is still so much to explore, so many stories waiting in shadowed corners, unheard and undocumented. But the first step is not grand or complicated. It is simple: to reconnect, to acknowledge, and to act.

On our way back, we hoped to end the day with Harisa—a winter delicacy that feels less like food and more like tradition. At Aali Kadal, the Harisa maker was already winding down, wrapping up his day and preparing for the next. We asked once, then again, and then a third time: “Harisa cha? Can we get Harisa?” His response came cold and final: “Waen gov warkaar pagah – Please come tomorrow.”

We walked away empty-handed, but not empty of feeling. What we carried with us instead was hope. Hope that lingers. Hope that binds. Hope that gives us a reason to return the next day—and to believe in a better tomorrow. Because Downtown is not a place we visit casually on Sundays. It is not a backdrop or a destination. It is a place that lives within us waiting to be acknowledged, waiting to be understood, waiting to be claimed again.

(To be Continued…)

Nazir Ganaie is an artist, filmmaker, and senior editor with Greater Kashmir.