In Jammu and Kashmir, education no longer merely reflects inequality; it authorises it. The classroom has ceased to be a neutral space of learning and has instead become a quiet theatre where social hierarchy is rehearsed every morning with the discipline of routine. What makes this hierarchy particularly grotesque is not simply poverty or infrastructural neglect – these have long histories – but the moral duplicity embedded within the system itself. A government teacher, salaried by the state to uphold public education, entrusts their own child to a private institution while standing daily before children whose parents have no such choice. This act, repeated across towns and villages, is not a personal failure of conscience alone; it is the symptom of a deeper structural rot. To read this condition through Karl Marx and John Rawls is not to impose theory upon reality, but to allow reality to speak in a language that exposes its injustice without euphemism.

Marx would have been unimpressed by the sentimental language often used to defend government schooling in Kashmir-talk of “constraints,” “background issues,” or “parental illiteracy.” For Marx, institutions do not fail accidentally; they function precisely as designed within a given social order. Education, in this sense, is not an equaliser suspended above class relations; it is one of the primary sites through which class relations are reproduced and normalised. The government school in Jammu and Kashmir functions less as a ladder of mobility and more as a mechanism of containment. It educates just enough to discipline, just enough to credential, but never enough to threaten the social distance between those who govern and those who are governed.

The decision of a government teacher to send their own child to a private school is often defended as rational individual choice. But Marx teaches us to be suspicious of choices that are socially patterned. When thousands of similarly placed individuals make the same “choice,” it ceases to be personal and becomes structural. This is not preference; but a class instinct. The teacher recognises, often intuitively, that the government school does not provide the linguistic capital, cultural exposure, pedagogical intensity, or competitive orientation required to survive in a marketised future. The teacher therefore exits the system privately while continuing to inhabit it professionally. This duality produces a peculiar form of alienation: the teacher is physically present in the government school but existentially absent from its promise.

Alienation here operates at multiple levels. The teacher is alienated from the product of their labour, no longer imagining their students as future equals but as permanent dependents of a compromised system. They are alienated from their own moral agency, forced to reconcile a public role with a private rejection of the institution they represent. Most devastatingly, the student is alienated from the very idea of education as emancipation. The child learns early-through gestures, silences, and unspoken comparisons-that even the teacher does not believe this space is sufficient for success.

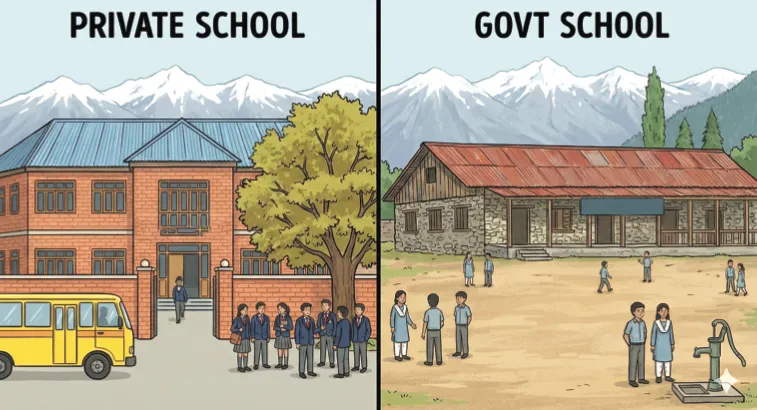

What emerges is not merely poor education but stratified education. Two children, both technically within the public system of the state, occupy radically different educational universes. One child studies in classrooms equipped with digital tools, English fluency, competitive benchmarking, and aspirational narratives of success. The other studies in overcrowded rooms where expectations are lowered in advance, where syllabi are “covered” rather than taught, and where success is framed as survival rather than excellence. To describe this disparity as unfortunate is to evade responsibility. It is, in Marxist terms, the reproduction of class relations under the guise of public welfare.

Rawls enters this picture not as a revolutionary but as a moral accountant, and even his restrained liberalism finds the system indefensible. Rawls’ theory of justice is premised on a simple but demanding intuition: social and economic inequalities are permissible only if they are arranged to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged and if positions are open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity. The education system of Jammu and Kashmir violates both conditions with remarkable consistency.

The notion of fair equality of opportunity collapses the moment we ask an uncomfortable but necessary question: can a child studying in a government school realistically compete with the child of a government teacher studying in a private institution? Competition here does not refer merely to examinations, but to the entire ecology of opportunity- language proficiency, confidence, exposure, mentorship, and institutional credibility. The answer, empirically and intuitively, is no. The competition is rigged not by malice but by design.

Rawls would insist that natural talents and social circumstances are morally arbitrary. No child deserves to be born into a marginalised family, just as no child earns the privilege of being born to educated, salaried parents. Justice demands that institutions compensate for these arbitrarinesses, not amplify them. Yet the government school system in Kashmir does precisely the opposite. It amplifies disadvantage by offering a diluted form of education to those who need robust intervention the most.

The moral scandal deepens when we recognise that those entrusted with administering this compensatory institution- the teachers- do not believe in it sufficiently to subject their own children to its conditions. This is not a psychological contradiction; it is an ethical one. Rawls’ veil of ignorance exposes it mercilessly. If a teacher did not know whether their own child would be born into a marginalised household or a salaried one, would they design an education system with such stark disparities? The answer is self-evident. The existing system can only be defended from positions of certainty and privilege, never from ignorance and fairness.

Defenders of the status quo often retreat to the language of inevitability. Private schools, they argue, exist everywhere; parental choice cannot be restricted; the state cannot compel belief. But this argument collapses under philosophical scrutiny. Rawls never argued for the abolition of inequality; he argued for its moral justification. The presence of private education is not inherently unjust. What is unjust is a public system so hollowed out that its own custodians flee from it. What is unjust is a state that tolerates this flight while continuing to invoke the rhetoric of equality.

This is where the question of standard becomes unavoidable. What, precisely, is the standard of education in government schools if those most familiar with it refuse to trust it with their own children? Standard is not merely a measure of syllabus completion or examination pass rates. It is a moral measure of confidence. A system believed in by no one cannot educate anyone. When teachers privately concede the inadequacy of their own classrooms, they transmit this concession-subtly but powerfully-to their students. Expectation collapses long before performance does.

The children who study in these government schools are not ignorant of this hierarchy. They see the difference in language, dress, confidence, and aspiration when they encounter private-school peers. They know, often without being told, that the race was unequal before it began. This knowledge does not always produce anger; more often, it produces resignation. And resignation is the most efficient form of social control. A resigned population does not rebel; it adapts downward.

Marx would describe this as ideological domination without coercion. The system does not need to violently exclude; it merely needs to normalise inequality as fate. Rawls would describe it as institutional injustice masquerading as neutrality. Together, they reveal a grim truth: the education system in Jammu and Kashmir no longer even pretends to be a site of justice. It functions as an administrative mechanism that sorts children according to social origin while preserving the moral innocence of those who benefit from it.

The question, then, is not whether this arrangement is systematic. It is whether we are willing to admit that injustice has been stabilised into routine. When a government teacher enters a classroom knowing that their own child is insulated from its limitations, something fundamental breaks. Teaching ceases to be an act of ethical investment and becomes mere employment. The classroom ceases to be a promise and becomes a holding space. And the state, by allowing this contradiction to persist, abdicates its most basic obligation: to ensure that birth does not determine destiny.

Systems of inequality do not survive merely through coercion or neglect; they endure because ordinary actors learn to live with contradiction. In Jammu and Kashmir’s education system, injustice has become sustainable precisely because it demands very little open cruelty. What it requires instead is silence, adjustment, and moral compartmentalisation. The government teacher who sends their child to a private school while teaching in a government one does not usually experience themselves as unjust. They experience themselves as pragmatic. And pragmatism, when repeated enough times, hardens into ideology.

This is where Marx’s insight becomes sharper and more unsettling. For Marx, ideology is not simply false consciousness imposed from above; it is lived reality experienced as common sense. The teacher tells themselves they are doing the best for their child, while also telling themselves that the children they teach are doing “well enough given their background.” Two different moral standards are quietly applied to two different classes of children. One is governed by aspiration, the other by mitigation. This is not hypocrisy in the theatrical sense; it is hypocrisy institutionalised into routine.

What makes this arrangement especially perverse is that it cloaks itself in the language of care. Teachers often speak warmly of their students, express concern for their hardships, and lament systemic constraints. Yet this concern rarely translates into a refusal of the system that produces those hardships. Compassion becomes a substitute for justice. The teacher pities the child but does not fight for a system in which pity would be unnecessary. Marx would recognise this as bourgeois morality at work-sympathy that soothes the conscience without threatening the structure.

Rawls, too, would find this moral psychology deeply troubling. His theory does not rely on heroic virtue; it relies on institutional fairness. It does not ask individuals to be saints, but it does require them to refuse arrangements they could not justify from behind the veil of ignorance. The problem in Jammu and Kashmir is not that individuals fail Rawls’ test unknowingly; it is that they fail it knowingly and proceed anyway. The teacher knows the system is unequal. They know their child’s advantage is not earned. They know the competition is unfair. Yet the system continues, unchallenged, because acknowledging injustice is easier than dismantling it.

One might argue that teachers alone cannot be burdened with moral responsibility for a failing system. That is true, but incomplete. Responsibility is not about sole causation; it is about participation. When a public servant continues to draw legitimacy, salary, and social authority from an institution they privately distrust, they become a stabilising agent of injustice. Their presence reassures the system that it can continue without reform. Their silence signals consent.

This consent has consequences that extend far beyond examination results. It shapes the moral imagination of students. Children educated in government schools learn early that authority figures do not fully believe in the spaces they inhabit. They learn that success lies elsewhere, that aspiration requires exit, that loyalty to public institutions is a liability rather than a virtue. This lesson is not taught explicitly, but it is absorbed nonetheless. Education here does not cultivate citizenship; it cultivates quiet disengagement.

The long-term effect is devastating. A society cannot sustain democracy when its public institutions are trusted only by those with no alternative. Government schools become residual spaces- places of last resort rather than collective commitment. Once an institution reaches this stage, reform becomes politically difficult because those with a voice have already exited. The poor remain, but the poor are rarely listened to. Inequality thus becomes self-reinforcing.

Rawls’ difference principle demands that inequalities work to the advantage of the least well-off. In Jammu and Kashmir, the opposite is true. The existence of private schools does not lift government schools through competition; it drains them of social pressure. When the children of teachers, administrators, and political elites are absent from public classrooms, there is no urgency to improve them. Neglect becomes administratively tolerable because it does not personally inconvenience those in power.

This is not merely a failure of governance; it is a failure of moral imagination. A just society requires its elites to share institutional fate with the masses, at least in foundational domains such as education. When this shared fate dissolves, so does the possibility of solidarity. Education ceases to be a common project and becomes a private investment strategy.

Marx would push this analysis further by reminding us that education under capitalism increasingly functions as a commodity rather than a right. Private schools do not merely offer instruction; they sell advantage. They monetise English fluency, confidence, networks, and future employability. Government schools, by contrast, are tasked with managing populations rather than producing excellence. This division mirrors the broader economic order, where surplus is concentrated and scarcity is administered.

The tragedy in Jammu and Kashmir is that this commodification operates within a region already scarred by conflict, marginalisation, and political instability. For children growing up in such conditions, education should be the most aggressively egalitarian institution the state offers. Instead, it is one of the first sites where inequality is encountered as destiny. The state, by failing to intervene meaningfully, communicates a brutal message: survival is your responsibility, not our obligation.

One might ask whether this system produces resistance. Occasionally, it does- but more often it produces accommodation. Students internalise modest aspirations. Parents lower expectations. Teachers normalise failure as realism. Over time, injustice loses its capacity to shock. This is perhaps the most dangerous outcome of all. A society that no longer recognises injustice cannot correct it.

Here Rawls and Marx converge in an unexpected way. Rawls, often caricatured as mild and procedural, would be appalled by a system that structurally denies fair opportunity while maintaining the fiction of equal competition. Marx, often caricatured as solely concerned with economic exploitation, would recognise the moral degradation produced by such a system- the erosion of responsibility, the fragmentation of ethical life, the reduction of education to credentialing.

The question that now confronts us is unavoidable: can an education system be called public when its own custodians refuse to trust it with their children? The answer, philosophically, is no. A public institution is not defined merely by funding or administration; it is defined by shared confidence. Where confidence is privatised, the institution ceases to be genuinely public. This brings us to the final and most uncomfortable recognition. The injustice of Jammu and Kashmir’s education system is not maintained by villains but by ordinary people making rational choices within an irrational structure. That is precisely why it is so difficult to dismantle. There is no single act of cruelty to condemn, no singular policy to repeal. There is instead a network of everyday decisions that collectively reproduce inequality.

Yet philosophy exists precisely to interrupt this normalisation. Marx reminds us that what appears natural is often historical, and therefore changeable. Rawls reminds us that what appears efficient may still be unjust. Together, they force us to ask not what is convenient, but what is defensible. To defend the current system, one would have to argue that children from marginalised families deserve weaker preparation, that unequal competition is acceptable, and that public institutions need not be trustworthy to those who run them. Few would make this argument openly. And yet, this is the argument enacted daily through practice.

The ultimate indictment, then, is not merely of the system but of the moral ease with which society lives alongside it. Injustice has not erupted; it has settled. It has become administrative, predictable, almost boring. And when injustice becomes boring, it becomes permanent. Unless the education system in Jammu and Kashmir is made good enough for those who govern it, it will never be good enough for those who depend on it. Until teachers can imagine their own children in the classrooms they occupy, those classrooms will remain spaces of managed inequality rather than sites of emancipation.

This is not a call for sentiment. It is a call for honesty. And honesty, in this case, leads to only one conclusion: the education system, as it stands, violates both the Marxian demand for structural justice and the Rawlsian demand for moral fairness. What remains is not reform rhetoric, but a choice- between continuing to administer inequality quietly or confronting it openly, at the cost of comfort.

History suggests that societies rarely choose confrontation voluntarily. But philosophy reminds us that avoiding it is itself a choice- one that future generations will inherit, not as theory, but as fate.

Zahid Sultan, Kashmir Based Independent Researcher, Having PhD in Political Science.