Industrial development is never accidental. It is the outcome of deliberate, consistent, and long-term policy vision. Economies that transformed into industrial powerhouses—Germany, Japan, South Korea, and later China—did not rely narrowly on fiscal concessions. They built enabling ecosystems anchored in robust infrastructure, industrial clustering, skills aligned with industry needs, regulatory simplicity, and institutional credibility. Entrepreneurs were granted stability, operational freedom, and confidence that rules would not shift unpredictably. Incentives existed, but only as supporting instruments within a coherent and predictable industrial strategy.

A similar pattern is evident within India. States that emerged as industrial leaders did not compete primarily on subsidies. They invested early in industrial estates, transport and logistics networks, reliable power supply, and governance systems that minimized uncertainty. Equally important was the strategic use of public procurement as a development tool. By enabling local enterprises to execute a substantial share of public infrastructure and development works, these states strengthened domestic capacity, retained capital locally, and nurtured competitive industrial champions. Complementing these measures, a national policy of imposing high customs duties on competing imports provided domestic industry essential protection during its formative years, allowing enterprises to scale up, build capabilities, and compete effectively over time.

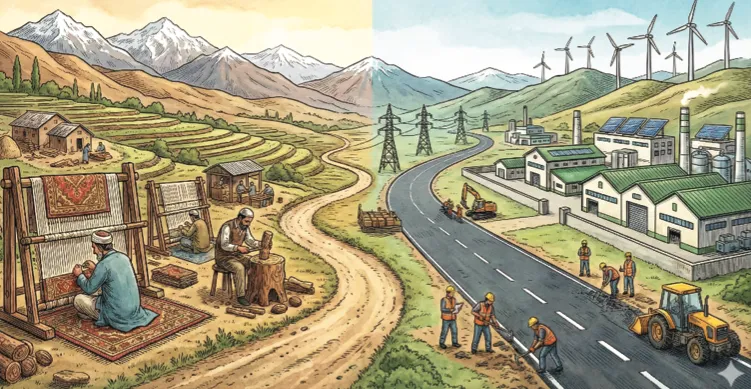

Jammu & Kashmir, however, largely remained outside this industrial growth trajectory. Despite a strong tradition in trade, handicrafts, and horticulture, the region failed to build a robust industrial base in the decades following Independence. For nearly three decades, industrial activity remained limited and predominantly public sector–driven. As late as 1975, the State had only about 5,000 industrial units, mostly tiny and small-scale, with private entrepreneurship existing only at the margins, constrained by remoteness, fragile connectivity, inadequate infrastructure, and the absence of a coherent industrial vision.

The first formal industrial policy promoting private entrepreneurship was introduced in 1978 by the then Chief Minister, Late Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah. With periodic modifications, it remained in operation until 1995, when a new framework was introduced. After a prolonged phase of Governor’s rule, the policy was refined and re-launched in 1998 under Dr. Farooq Abdullah’s Government to address emerging economic challenges. In 2002, Prime Minister Shri Atal Bihari Vajpayee announced a Central Industrial Policy for J&K. While significant in intent and helpful in attracting fresh investment, it focused largely on new units but failed to pay attention to rehabilitating existing industries, leading to uneven growth. The simultaneous operation of State and Central policies created confusion, prompting the Mufti Mohammad Sayeed–led government to introduce a comprehensive industrial policy in 2004 that integrated both State and Central incentives under a unified framework.

These successive policies, despite good intent, suffered from weak continuity, limited institutional readiness, and inconsistent implementation. Some relied excessively on incentives without infrastructure; others launched ambitious schemes without adequate administrative or budgetary support. Rehabilitation and expansion of existing units remained peripheral, resulting in frequent policy shifts without sustained transformation. Consequently, J&K did not integrate meaningfully into India’s industrial expansion, leaving its industrial base fragile and fragmented.

The structural weaknesses were compounded by the deterioration of law and order after 1989. Prolonged instability—marked by nearly 2,500 days of business disruptions—severely disrupted production, logistics, and market access. Capital erosion, rising indebtedness, and loss of entrepreneurial confidence followed. Many otherwise viable units slipped into sickness, risk-taking declined sharply, and policy responses failed to adequately address this exceptional context.

In more recent years, structural policy changes further weakened local industry. The withdrawal of VAT exemptions following GST implementation removed a critical protective cushion for local units. Simultaneously, changes in public procurement—particularly the shift to GeM and mandatory e-procurement— marginalized enterprises lacking scale, capital, or digital readiness. The withdrawal of toll tax on imports from other states, while curtailing government resources, removed a natural cost equalizer that had supported local competitiveness.

These measures and many more left most of the units sick or marginally operational, depleting capital and causing loan defaults. The situation worsened with implementation of the SARFAESI Act in 2017, which empowered banks to take possession and auction collaterals, including ancestral properties. For small and medium entrepreneurs, financial stress turned into social and psychological distress, extinguishing appetite for reinvestment or expansion.

Over the last five to six years, the traditional developmental bond between industry and administration weakened further. The government’s role shifted from facilitator to regulator, eroding trust, reducing handholding, and widening the gap between policy intent and ground realities. Inter- and intra-departmental cohesiveness also suffered.

This legacy has created a counterproductive scenario where multiple frameworks—the Industrial Policy 2016–26, Industrial Policy 2021–30, and the New Central Sector Scheme 2021—operate simultaneously. Rather than clarity, this multiplicity has created confusion, overlapping provisions, inconsistent interpretation, and uneven implementation. Divergent interpretations of several provisions by separate directorates in Kashmir and Jammu have undermined uniformity within a single Union Territory, adding unpredictability for entrepreneurs.

Despite sustained efforts by the apex industrial chambers to persuade the authorities to remove ambiguities in the existing policies, no tangible progress was achieved until the issue was taken up and actively pursued with the Chief Minister, Omar Abdullah. The chambers emphasized the need to replace multiple overlapping policies with a single, comprehensive, and uniformly applicable industrial policy framework. Recognizing these shortcomings and acting on the Chief Minister’s directions, the Industries and Commerce Department issued a notice on 23 December 2025 proposing a review of the Industrial Policy 2021–30. The proposed exercise aims to adopt best practices from other States and Union Territories, address region-specific requirements, and invite suggestions from stakeholders.

However, the proposed policy revision comes at a time when the other two industrial policies are being phased out. While the Industrial Policy 2016–26 is set to expire by the end of the current financial year, the 28,400-crore New Central Sector Scheme launched in 2021 is reportedly considered fully utilized on the basis of project registrations. A closer examination reveals that a disproportionate number of these registrations are concentrated in just two to three districts, resulting in inequitable regional growth—an outcome clearly inconsistent with the intent of the Central Government, which extended the package for balanced industrial development across the entire Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Moreover, most registered projects remain far from actual implementation and, at the prevailing pace, may take decades to materialize. Stakeholders contend that incentives have effectively been ring-fenced without any regard for and sufficient linkage to district- and division-wise balance, actual execution, or employment generation, thereby denying genuinely operational units fair access under the principle of first-come, first-served basis. In this context, the onus squarely lies on the UT Government to take timely and corrective measures and to effectively engage with the Central Government to address these anomalies and realign the scheme with its original objectives.

It must be clear that incremental amendments to an already layered policy framework cannot address the underlying structural deficiencies. Jammu & Kashmir now needs a fundamental rethinking of its industrial strategy—one that prioritizes simplicity, uniformity, time-bound implementation, and outcome-driven support over piecemeal fixes. At present, nearly 60 per cent of the Union Territory’s economy is driven by the services sector, a level of dependence that poses serious risks to long-term sustainability and steadily undermines traditional industries and manufacturing capabilities. Simultaneously, imports from other States and overseas markets continue to rise with each passing day. This trend underscores the urgent need to strengthen domestic manufacturing capacity by designing and producing the goods we consume locally, while also building scale for export-oriented manufacturing. A substantial expansion of the manufacturing base is therefore essential to restore economic balance, generate durable employment, and ensure resilient and self-reliant growth.

A fresh, consolidated industrial policy must therefore be target-driven, locally anchored, and firmly focused on industrial promotion rather than mere incentive distribution. Its objectives should be clearly defined and measurable, aimed at the consolidation of existing industries to ensure optimal capacity utilization and sustained capacity building. The policy should prioritize the generation of sustainable employment, the availability of ready-to-use infrastructure for prospective units, and the creation of a resilient and competitive industrial ecosystem. Incentives should play a facilitative role and be structured for automatic, time-bound reimbursement with minimal physical interface.

Infrastructure must form the backbone of the proposed policy, with equitable regional and sub-regional distribution as a core principle. Industrial land, reliable power, rooftop solar systems, water, waste management, logistics, and digital connectivity are essential for balanced industrial development. New industrial estates and the systematic up-gradation of existing ones must be time-bound, outcome-oriented, and strategically located to correct regional imbalances. Estates should be fully serviced and operational, enabling industries in the unorganised sector to transition to organised spaces. Clustering, shared infrastructure, and common facilities will improve efficiency, reduce costs, and strengthen regional competitiveness.

Organised industrial estates should provide an enabling environment by combining fiscal incentives, simplified regulations, and world-class infrastructure. Units should benefit from exemptions on license and renewal fees, stamp duty, and other levies, with streamlined processes via single-window and digital clearances, minimal licensing, self-certification, and time-bound approvals. Estates must offer plug-and-play plots, built-up spaces, and shared facilities to reduce transaction costs, ensure policy certainty, and foster a business-friendly environment. This ecosystem will support competitive enclaves for manufacturing, IT, high-value services, horticulture, and other strategic sectors, driving investment, innovation, and inclusive industrial growth.

Trust-based regulation is equally vital to creating a truly business-friendly ecosystem. Compliance should be presumed, with self-declaration and post-facto verification replacing multiple pre-approvals and NOCs, reducing unnecessary administrative burdens. Digitization of processes, minimal physical interfaces, and risk-based inspections will significantly lower transaction costs, streamline operations, and cut delays. By simplifying regulatory procedures, entrepreneurs can focus more on production, innovation, and market expansion, rather than administrative compliance.

Such a system not only enhances Ease of Doing Business by providing clear, predictable, and time-bound approvals, but also improves Ease of Living for business owners by reducing stress, travel, and paperwork. Access to single-window digital platforms, online tracking of approvals, and faster grievance redressal will allow entrepreneurs to plan and operate with confidence, ensuring that industrial estates are not just spaces for manufacturing, but vibrant, supportive ecosystems that promote sustainable growth, innovation, and inclusive economic development.

The new industrial policy must place strong emphasis on the creation and retention of sustainable employment within enterprises. Incentives linked to labour retention and worker welfare—such as partial support for provident fund and Employees’ State Insurance contributions—should be incorporated to encourage stable, formal employment and improve workforce security. Beyond retention, the scheme should actively incentivize existing enterprises to create additional employment opportunities, even if modest in scale. For example, absorbing one or two new employees per enterprise can cumulatively generate substantial employment across the Union Territory within a short span of time.

Such targeted employment schemes should be outcome-driven, with clear metrics and monitoring to ensure tangible results. By linking incentives directly to the number of new jobs created or retained, enterprises will have a direct financial and operational motivation to expand their workforce. This approach not only strengthens the formal labour market but also enhances workforce skill development, supports inclusive growth, and ensures that industrial expansion translates directly into sustainable livelihoods for the local population.

Public procurement must be repositioned as a strategic development lever to strengthen local industrial capacity and foster inclusive economic growth. Over the years, local enterprises in Jammu & Kashmir have been systematically excluded from participation in government contracts and major developmental projects, leading to underutilization of regional manufacturing potential. At the same time, departments have increasingly relied on goods imported from outside the Union Territory, often encountering issues with quality, pricing, and timely delivery.

To address these challenges, public procurement should actively encourage meaningful participation of local enterprises, ensuring that government expenditure circulates within the regional economy, generates employment, and strengthens domestic capabilities. The J&K State had earlier conceptualized pooling of industrial goods requirements under the 1978 Industrial Policy and established J&K SICOP to operationalize this approach. Strengthening this framework through rigorous monitoring, competitive pricing, robust quality testing, and equitable distribution will improve standards of locally manufactured goods, build enterprise capacity, and instill confidence among government buyers.

Equally important is marketing assistance to local units, especially in a geographically and economically unique region like J&K. Exposure to external markets through sponsored participation in national and international exhibitions, trade fairs, and structured brand-promotion initiatives can significantly expand their reach, attract new clients, and enhance competitiveness. Providing such support will not only boost sales and profitability for local enterprises but also reinforce their role in creating a resilient industrial ecosystem, driving regional development, and positioning J&K as a hub for quality manufacturing and innovation.

A critical issue that continues to undermine local enterprises is delayed payments by government departments. There have been instances where departments have withheld substantial payments due to enterprises, creating severe financial stress and resulting in failures to meet banking obligations, interest, and installment payments. Despite the existence of the Delayed Payments Act, prompt enforcement has been lacking. Strengthening this Act with clear guidelines, stricter timelines, and effective monitoring mechanisms is essential to protect enterprises, maintain financial stability, and ensure that participation in public procurement remains viable and attractive for local units.

The policy must also allow enterprises to evolve. Flexibility to modify business structures, change product lines, and respond to market conditions should be embedded, alongside a dignified and efficient exit framework for unviable units. Smooth exits enable asset redeployment, fresh investment, and prevent industrial stagnation.

Equally critical is the consolidation, revival, and rehabilitation of existing and sick industrial units. Structured mechanisms—including financial restructuring, working capital support, technology up-gradation, and market facilitation—must assist viable but stressed units, while unviable units should be enabled to exit smoothly without prolonged disruption. To support these efforts, a dedicated corpus should be created to provide soft loans and concessional financial assistance to enterprises seeking to revive operations, modernize technology, or expand capacity. The Government of India, through its Task Force on MSME recommendations, has already approved a contribution of ₹100 crore towards such a corpus, which can serve as a foundation for sustained support.

The rehabilitation framework under Government Order 47-Ind of 1999, with slight modifications to suit current industrial realities, remains a suitable and tested mechanism to guide restructuring and revival. Linking the corpus with this framework will ensure timely, transparent, and outcome-oriented financial assistance. By combining financial support with technology up-gradation and market facilitation, the policy can not only preserve existing industrial capacities but also strengthen enterprise resilience, safeguard employment, and enhance the competitiveness of local units in regional, national, and global markets.

Fiscal incentives must be designed to flow seamlessly, with minimal physical interface, ensuring ease of access and reducing administrative burden for enterprises. For operational units, this should include automatic exemptions from license fees, renewal fees, stamp duty, court fees, and pollution control consents to establish and operate fee, additional premium demands on change of constitution, among others. Interest subvention on working capital and term loans should be directly payable to banks through a robust mechanism, relieving enterprises of additional financial stress. Additionally, a mechanism for SGST value-addition refunds should be established so that units do not have to make upfront payments; instead, it should be made from a dedicated notional fund.

However, for prospective units and those undertaking substantial expansion, targeted handholding is necessary. Capital Investment Subsidy and other incentives can serve as margin money to facilitate bank financing, enabling new and expanding enterprises to access credit efficiently and scale operations without undue financial hurdles.

Finally, stability and predictability must anchor the policy. Industrial investments require long horizons; frequent rule changes erode confidence. Uniform interpretation, transparent administration, and automatic, time-bound incentives are essential.

The challenge ahead is as much institutional as it is policy-driven. The focus must shift from control to facilitation, from regulation to partnership. Jammu & Kashmir’s industrial underperformance is not a reflection of entrepreneurial weakness but of an ecosystem that has historically constrained growth.

The present moment presents a rare and critical opportunity for both policymakers and industry chambers to actively shape the future of the region’s industry. After years of limited engagement, apex chambers are now invited to contribute their insights. Owing to mushrooming of self-serving organisations and chapters, it is essential that the policy reflect the perspectives of organizations truly grounded in the field—those with firsthand, practical experience—rather than relying on theoretical or paper-based recommendations. Their input must guide a framework that responds to real-world challenges and catalyzes genuine industrial revival.

By leveraging this collaboration, the proposed policy revision can establish a consolidated, locally anchored, and target-driven industrial framework. Rooted in robust infrastructure, trust-based regulation, flexibility, and long-term stability, such a framework has the potential to transform Jammu & Kashmir’s industry into a resilient engine of sustainable employment, entrepreneurial growth, and enduring economic prosperity.

Shakeel Qalander, prominent business leader and a civil society animator